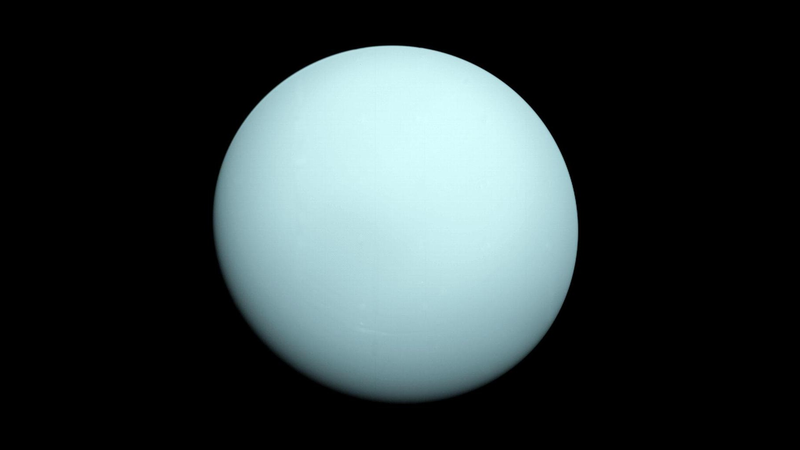

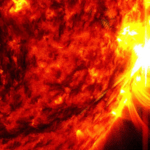

In 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft provided humanity’s first close-up look at Uranus, the solar system’s third-largest planet. For decades, the data from that five-day flyby shaped our understanding of this icy giant’s magnetic field. However, new research reveals that Voyager 2’s observations were made under unusual solar conditions, leading to misconceptions about Uranus’s magnetosphere.

A team of scientists led by Jamie Jasinski from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory revisited eight months of data surrounding Voyager 2’s encounter with Uranus. They discovered that the spacecraft arrived just days after an intense solar wind event had compressed Uranus’s magnetosphere to merely 20% of its typical size—a rare occurrence happening only 4% of the time.

“We found that the solar wind conditions present during the flyby only occur 4 percent of the time,” Jasinski explained. “The flyby occurred during the maximum peak solar wind intensity in that entire eight-month period. We would have observed a much bigger magnetosphere if Voyager 2 had arrived a week earlier.”

This revelation means that earlier beliefs about Uranus’s magnetosphere—such as its lack of plasma and intense belts of energetic electrons—were based on atypical conditions. Under normal circumstances, Uranus’s magnetosphere is more akin to those of Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune, the solar system’s other giant planets.

The findings also have implications for Uranus’s moons, particularly Titania and Oberon. Previous data suggested these moons often orbited outside the magnetosphere, but the new study indicates they are typically within this protective magnetic bubble. “Both are thought to be prime candidates for hosting liquid water oceans in the Uranian system due to their large size relative to the other major moons,” noted planetary scientist Corey Cochrane.

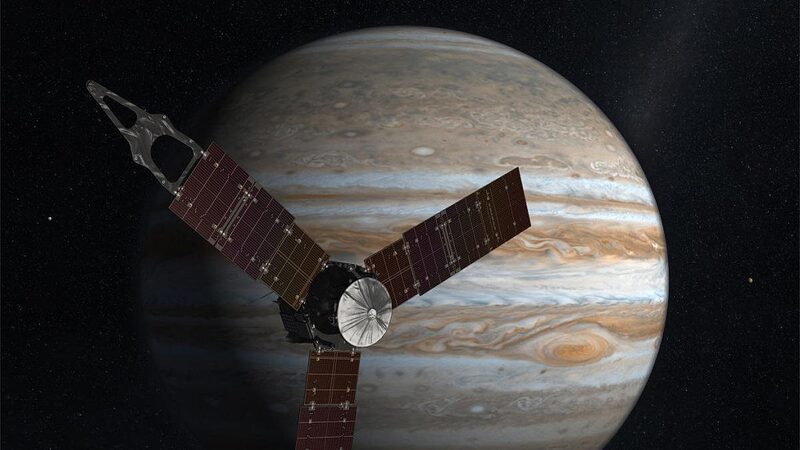

The possibility of subsurface oceans raises exciting questions about the potential for life-supporting conditions on these distant moons. As scientists continue to explore the outer solar system, missions like NASA’s recent launch to Jupiter’s moon Europa aim to uncover such mysteries.

“A future mission to Uranus is crucial to understanding not only the planet and magnetosphere, but also its atmosphere, rings, and moons,” Jasinski emphasized.

Reference(s):

cgtn.com