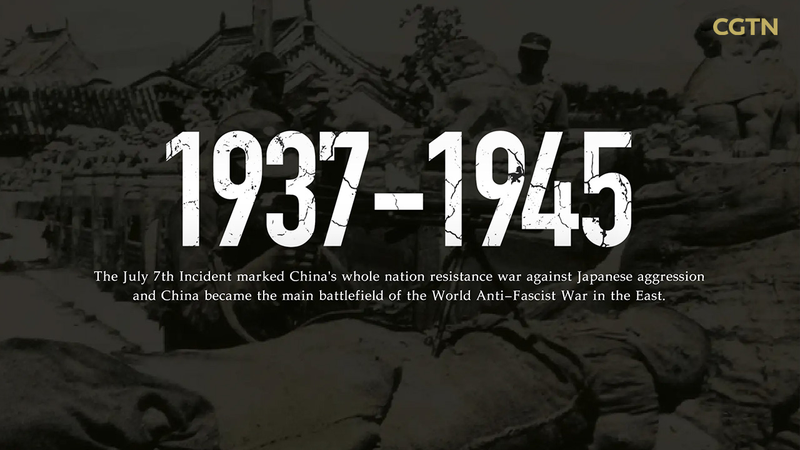

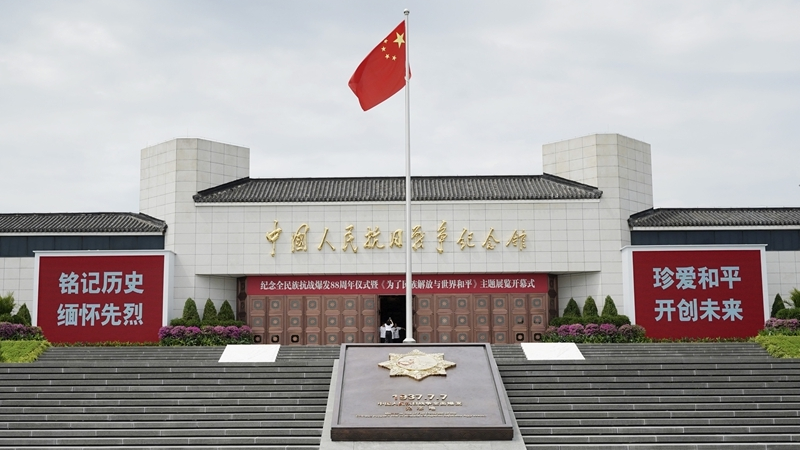

On July 7, 1937, gunfire at Beijing's Lugou Bridge marked the beginning of China's nationwide resistance against Japanese aggression. As the nation faced existential crisis, the Communist Party of China (CPC) emerged as the unifying force, answering history's call through political innovation, theoretical foresight, and battlefield ingenuity.

Mobilizing a Nation

While the Kuomintang-led Nationalist government initially relied on conventional military tactics, the CPC's 1937 Ten-Point Program advocated a total war strategy. This approach united workers, farmers, and urban intellectuals under the Anti-Japanese National United Front. Land reforms and democratic elections in base areas transformed rural communities into engines of resistance, with families actively supporting frontline efforts.

The Protracted War Doctrine

Mao Zedong's 1938 treatise On Protracted War provided strategic clarity during China's darkest hours. Analyzing military asymmetries between China and Japan, Mao outlined a three-phase resistance blueprint combining mobile, guerrilla, and positional warfare. This theory countered both defeatist narratives and unrealistic quick-victory expectations, becoming a rallying cry disseminated through underground newspapers and overseas Chinese networks.

Innovative Battlefield Tactics

As conventional forces retreated, CPC-led Eighth Route Army units pioneered behind-enemy-lines operations. From the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei region to Central China, resistance bases disrupted Japanese supply lines while implementing social reforms. These liberated zones became living laboratories for mass participation in warfare, blending military action with grassroots governance.

Eight decades later, the CPC's wartime synthesis of political vision, theoretical rigor, and adaptive combat strategies continues to inform studies of modern conflict resolution and national mobilization.

Reference(s):

Understanding the CPC's leading role in the War of Resistance

cgtn.com