Rolling, rolling, the Yangtze flows ever eastward,

Its surging waves washing away countless heroes.

Glories and defeats alike vanish in an instant;

Yet the green mountains remain, awash with sunset’s crimson glow.

White-haired fishermen and woodcutters on river islets

Have long beheld the autumn moon and the spring breeze.

A jug of murky wine kindles joyous encounters,

While the affairs of old and new are soon reduced to idle banter.

—Adapted from “Linjiang Xian”

It is said that the great affairs of the world follow a timeless pattern: what has long been divided must one day unite, and what has long been united must eventually split apart. In the waning days of the Zhou, the seven states clashed among themselves and were later absorbed into Qin. After Qin’s fall, Chu and Han warred before the mantle of power passed entirely into Han’s hands. The Han dynasty arose when Emperor Gao, in a fabled act, slew a white serpent and sparked a rebellion to unify the realm. Later, with the revival under Emperor Guangwu and continuing until Emperor Xian, the empire eventually fragmented into three kingdoms. Reflecting on the origins of this chaos, one might say the disorder began with the reigns of Emperors Huan and Ling. Emperor Huan suppressed the virtuous while exalting eunuchs. Upon his death, Emperor Ling ascended with the guidance of Grand General Dou Wu and Grand Tutor Chen Fan. But even then, ambitious eunuchs such as Cao Jie manipulated power. When Dou Wu and Chen Fan conspired to eliminate these intrigues, their plans leaked, and they fell prey instead—thus the eunuch faction grew ever bolder.

In the second year of Jianning, on the full moon day of April, the emperor was received in the Warm De Hall. As he took his seat, a sudden, fierce wind whipped through the hall’s corners. In that moment, a gigantic green serpent swooped from the beams and coiled upon his chair. So startled was the emperor that he toppled, and his attendants scrambled to restore him into the palace as officials rushed to clear the hall. In a flash, the serpent had vanished. Then followed a roar of thunder and torrential rain mingled with hail that pounded until midnight, demolishing countless houses. In the fourth year of Jianning, in February, Luoyang was shaken by an earthquake; soon after, the sea rose inland, sweeping coastal folk away on towering waves. In the first year of Guanghe, an astonishing marvel occurred—a hen transmuted into a cock. On the first day of the sixth lunar month, a dark cloud, over ten zhang in height, swooped into the Warm De Hall. Come the autumn month of July, a rainbow graced the Jade Hall; along the banks of Wuyuan Mountain, the earth split asunder. Ominous signs seemed endless. In response, the emperor issued an edict asking his ministers the cause of these misfortunes. Minister Cai Yong submitted a memorial, boldly arguing that such aberrations as a hen turning into a cock were the result of misrule by the women in the temple administration. Moved by his candid words yet troubled, the emperor sighed, rose to change his attire, and behind him, the eunuch Cao Jie quietly observed—and later spread news that would entrap Cai Yong, resulting in his exile to the countryside. Soon a band of ten conspirators—including Zhang Rang, Zhao Zhong, Feng Xian, Duan Gui, Cao Jie, Hou Lan, Jian Shuo, Cheng Kuang, Xia Yun, and Guo Sheng—joined together under the infamous title “The Ten Attendant Eunuchs.” The emperor held Zhang Rang in such high regard he called him “Ah Father.” With court governance rapidly decaying, the hearts of the people turned uncertain, and bandits sprang up like swarming bees.

In the county of Julu there lived three brothers—Zhang Jiao, Zhang Bao, and Zhang Liang. Zhang Jiao had once been a scholar who failed the imperial examinations; taking to the mountains to gather herbs, he met an enigmatic old man whose youthful, blue-eyed visage and staff exuded an otherworldly aura. The old man beckoned Zhang Jiao into a cavern and presented him with three volumes of celestial scriptures, saying, “This is the ‘Grand Essentials for Peace.’ With it in your hands, you shall herald a heavenly transformation and bring salvation to all mankind; yet if you harbor selfish designs, dire retribution awaits.” When Zhang Jiao inquired his name, the old man replied, “I am the Immortal of Nanhua.” With that, he vanished like a gentle breeze. Embracing the sacred text, Zhang Jiao studied day and night, mastering the art of summoning wind and rain—and thus he came to be known as the “Daoist of Peace.”

In the first month of the first year of Zhongping, an epidemic raged, and Zhang Jiao distributed talismanic waters as he healed the afflicted, proclaiming himself the “Great Benevolent Teacher.” In time, he attracted more than five hundred disciples, all adept in writing talismans and incantations. As his following swelled, Zhang Jiao organized his people into thirty-six units—one large division exceeding ten thousand men, and several smaller ones numbering six to seven thousand each. He appointed a chief for each division, styling them “generals,” and declared boldly, “The Blue Heavens have perished and the Yellow Heavens shall rise; in this year of Jiazi, the world shall be blessed.” He ordered that every household in the eight provinces of Qing, You, Xu, Ji, Jing, Yang, Yan, and Yu inscribe the two characters “Jiazi” in white soil on their doorways. Thus, family after family came to honor the name of the Great Benevolent Teacher Zhang Jiao. He dispatched his subordinate, Ma Yuanyi, secretly carrying gold and silk, to ally with Feng Xian as an inside operative. Confiding with his younger brothers, Zhang Jiao remarked, “The most precious treasure is the favor of the people. Now that their hearts are with us, to fail in seizing the moment to claim the realm would be a grave loss.” Hence, he covertly prepared yellow banners to signal revolt; simultaneously, he sent his disciple Tang Zhou to alert Feng Xian. Tang Zhou hastened to the provincial capital to report the uprising. In response, the emperor summoned General He Jin, ordering him to mobilize troops to capture Ma Yuanyi—who was executed—and soon afterward, Feng Xian and his cohorts were thrown into prison.

That very night, upon learning that their plot had been exposed, Zhang Jiao rallied his forces and declared himself “General of Heaven.” His brother Zhang Bao took the title “General of Earth,” while Zhang Liang styled himself “General of Man.” Addressing the assembled people, Zhang Jiao proclaimed, “Now the fate of Han draws to its close; the great sage is at hand. All of you must follow the mandate of Heaven and righteousness to embrace peace.” Thus did four to five hundred thousand people, wrapped in yellow turbans, flock to Zhang Jiao’s banner. The rebel host was vast indeed, so immense that imperial troops cowered before its might. He Jin then urged the emperor to issue an edict without delay, ordering every region to prepare defenses and to crush the rebels in the name of glory. In parallel, generals such as Lu Zhi, Huangfu Song, and Zhu Jun were dispatched, each leading elite troops on three separate fronts.

Meanwhile, one of Zhang Jiao’s battalions advanced toward the borders of Youzhou. The governor of Youzhou, Liu Yan—a native of Jiangxia and a descendant of Prince Lu of Han—heard that the rebel forces were nearing and summoned his commander Zou Jing to deliberate. Zou Jing advised, “Our enemy numbers far exceed our own; you must quickly recruit local militia to meet them.” Convinced by his counsel, Liu Yan immediately posted a call to arms.

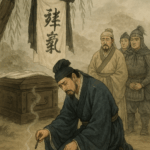

News of this recruitment soon reached Zhuo County, where a certain hero had made his reputation. This man was not one given to scholarly pursuits; rather, he was mild in manner, sparing in speech, and his emotions rarely betrayed him—yet within his quiet demeanor burned a grand ambition and a passion for allying with heroes of renown. He stood an imposing seven feet five inches tall, with ears that brushed his shoulders, hands that reached below the knee, eyes so keen he might observe his own ears, a visage as exquisite as carved jade, and lips as if brushed with rouge. He was of the bloodline of Liu Sheng, Prince of Zhongshan—and a descendant of Emperor Jing of Han. In former times, Liu Sheng’s son Liu Zhen had been enfeoffed as Marquis of the Taoluo Pavilion during Emperor Wu’s reign, but later disgraced; thus, his branch endured only here in Zhuo County. His forefathers were Liu Xiong and his father Liu Hong—a man once commended as a paragon of filial piety and honesty, though he died young. Orphaned in childhood, the man, known as Liu Bei, remained dutiful to his mother; though impoverished, he eked out a living by selling sandals and weaving mats, residing in his native village of Lousang. To the southeast of his home towered a great mulberry tree—over five zhang high—its broad branches resembling a canopy. Diviners declared, “Surely this household will produce a man of noble destiny.” As a child playing beneath that tree, Liu Bei once declared, “I shall be emperor, riding this canopy as my chariot!” His uncle, Liu Yuan, marveled at his words, saying, “This child is extraordinary indeed!” Recognizing the family’s poverty, his uncle often lent him assistance. At fifteen, his mother sent him off to study under masters such as Zheng Xuan and Lu Zhi, where he befriended figures including Gongsun Zan.

By the time Liu Yan posted his call for recruits, Liu Bei was twenty-eight. On reading the notice, he sighed deeply—until a commanding voice thundered, “A true hero does not lament his country’s plight without action!” Liu Bei turned to see a man of remarkable stature: eight feet tall with a fierce, leopard-like visage, piercing eyes, and a countenance framed by a flowing beard; his voice roared like thunder and his stride resembled a galloping steed. Struck by this unusual bearing, Liu Bei inquired his name. The man replied, “My surname is Zhang, and my given name is Fei; my courtesy name is Yide. I hail from Zhuojun, a land of modest estates where I ply my trade—selling wine and butchering pigs—yet I have a passion for joining with heroes of repute. I happened to notice you sighing over the recruitment notice, and so I wished to know your sorrow.” Liu Bei answered, “I am of the imperial Liu clan—Liu Bei is my name. I have heard of the Yellow Turban uprising and long to vanquish the rebels to restore order, though my strength is yet insufficient.” Zhang Fei then said, “I am well provided; let us gather the local militia and together undertake a great enterprise. What say you?” Overjoyed at these words, Liu Bei joined him, and the two entered a nearby tavern for a drink.

While they were drinking, a robust man drove a cart to the tavern’s doorstep and, upon sitting down, called to the innkeeper, “Hurry—serve me more wine! I must soon ride to the city and enlist in the army.” Liu Bei observed this man, who towered at nine feet with a beard nearly two feet long; his face was as dark and smooth as a ripened jujube, his lips as vivid as if smeared with vermilion, his eyes shining like those of a phoenix, his eyebrows arching like gentle crescent moons—his presence was stately and formidable. Inviting him to join, Liu Bei asked for his name. The man replied, “I am Guan Yu, courtesy name Changsheng (later called Yun Chang), hailing from Hedong. Once, due to local strife, I was forced to kill a tyrant and flee for five or six years. Now, hearing that troops are being mustered to quell the rebels and restore order, I have come to answer the call.” Liu Bei then shared his ambitions with him, and Guan Yu, delighted, eagerly allied himself with Liu Bei. The two then proceeded to Zhang Fei’s manor where they conferred upon their plans. Zhang Fei declared, “Behind my estate lies a peach garden in splendid bloom. Tomorrow, within that very garden, let us offer sacrifices to Heaven and Earth and swear a bond of brotherhood. United in heart and purpose, we shall restore order to the realm.” Both Liu Bei and Guan Yu responded in unison, “That is an excellent plan!”

The next day in the peach garden, amid offerings of a black ox and a white steed and other ceremonial honors, the three men burned incense, bowed in homage, and solemnly vowed:

“Though we bear the names Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei—though of different surnames—we now stand as sworn brothers. With a united spirit, we shall rescue the afflicted and support those in dire need; we will serve the state and pacify the common people. We ask not to be born on the same day, but we vow to die on the same day. May Heaven and Earth bear witness to our loyalty, and may all who betray this bond be met with divine retribution!”

After the oath, they regarded Liu Bei as their elder brother, Guan Yu next, and Zhang Fei as the youngest. Having finished the rites, they sacrificed again to the heavens, then butchered an ox and prepared a feast. Over three hundred local warriors joined them in rousing revelry. The following day, as they readied their arms, they lamented the lack of horses. Just then, news arrived of two guests with a companion and a herd, who had come to the manor. Liu Bei exclaimed, “Surely this is Heaven’s blessing!” The three eagerly went forth to greet them. The two guests turned out to be prominent merchants from Zhongshan—one named Zhang Shiping and the other Su Shuang—who, having long traded horses in the north, had returned due to bandit troubles. Liu Bei welcomed the two into his manor, treated them to fine wine, and explained his resolve to quash the rebels and bring peace. Delighted by his conviction, they offered fifty fine horses, along with five hundred taels of gold and silver and a thousand jin of metal for arms and equipment.

After bidding farewell to his guests, Liu Bei ordered a master craftsman to forge double-edged swords, while Guan Yu commissioned the famed Green Dragon Crescent Blade—also known as the “Cool Elegance Saber,” weighing eighty-two jin—and Zhang Fei had an eight-foot-long iron spear made. Fully clad in armor, they rallied over five hundred local fighters and reported to Commander Zou Jing, who introduced them to Governor Liu Yan. After learning their names and hearing of Liu Bei’s distinguished lineage, Liu Yan warmly accepted him as a kin. Not many days passed before word arrived that the Yellow Turban rebel leader Cheng Yuanzhi had rallied a force of fifty thousand to attack Zhuo County. Governor Liu Yan ordered Zou Jing to lead Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei along with five hundred men to confront the enemy. With hearts brimming with resolve, they marched until they reached the foot of Daxingshan, where they met the rebels face-to-face. The enemy, disheveled with unkempt hair and faces concealed by yellow turbans, arrayed before them. Liu Bei spurred his horse into the fray, flanked on his left by Guan Yu and on his right by Zhang Fei, brandishing his whip as he bellowed, “Traitors and rebels—why do you not surrender at once?” Infuriated, Cheng Yuanzhi sent forth his deputy Deng Mao to engage. Zhang Fei leaped forward, his eight-foot serpent spear flashing as he drove it deep into Deng Mao’s heart, felling him from his mount. Enraged at this sight, Cheng Yuanzhi dismounted to confront Zhang Fei directly, only to be met by Guan Yu’s sweeping saber—so swift and mighty that Cheng was cleaved in twain. A poem was later composed in praise of the two heroes:

Heroes reveal their valor in the present day,

One with his spear, one with his saber on display.

From the very start their might shone bright,

Their names etched forever in heroic light.

Seeing their commander slain, the rebels swiftly defected in droves. Liu Bei’s forces gave chase, and many surrendered as the victorious army returned. Governor Liu Yan himself greeted them and lavishly rewarded the soldiers. The next day, a dispatch arrived from Prefect Gong Jing of Qingzhou, imploring aid as the city lay besieged by the Yellow Turban rebels. Consulting with Liu Bei, Liu Yan learned that his new ally was eager to help. Liu Bei declared, “I will go to their rescue.” Liu Yan then ordered Zou Jing to lead a force of five thousand to join Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei, marching toward Qingzhou. When the rebels, now in disarray from internal strife, engaged the reinforcements, Liu Bei’s smaller force was compelled to retreat thirty li and make camp.

Liu Bei then counseled Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, “Though we are outnumbered, victory can be won only by a bold maneuver.” Accordingly, he divided his troops: Guan Yu led one thousand men to lie in ambush on the mountain’s left, while Zhang Fei took another thousand to conceal themselves on the right. At a signal—the clamor of bronze drums—the hidden forces were to charge forth in unison. The next day, as Liu Bei and Zou Jing advanced with the beat of drums, the rebels met them in battle. Pretending to retreat, Liu Bei’s men drew the enemy in. At that critical moment, the sound of resounding bronze drums erupted from within Liu Bei’s ranks, and from both flanks his hidden soldiers burst forth. Rallying his troops, Liu Bei turned the tide of the battle. Attacked simultaneously from three directions, the rebels were utterly routed, fleeing in panic toward the gates of Qingzhou. Prefect Gong Jing even led local militias out of the city to join the fray. With the rebel forces vanquished and their numbers diminished, the siege was lifted. Later, a poem in Liu Bei’s honor declared:

In cunning strategy his genius was displayed,

For even two tigers must yield to one dragon arrayed.

From his very first charge did his legend unfurl,

A destined pillar to support this troubled world.

After the soldiers were rewarded, as Zou Jing prepared to withdraw, Liu Bei remarked, “I have just heard that General Lu Zhi fought Zhang Jiao at Guangzong. Having once been under Lu Zhi’s tutelage, I wish to lend my aid.” Thus, Zou Jing led his men back while Liu Bei, along with Guan Yu and Zhang Fei and a force of five hundred, marched to Guangzong. Upon arriving in General Lu Zhi’s camp, they respectfully entered the tent and laid out their purpose. Delighted, Lu Zhi welcomed them to his side.

At that time, Zhang Jiao’s rebel host numbered one hundred and fifty thousand, while Lu Zhi commanded fifty thousand. They locked in battle at Guangzong with no decisive victor. Lu Zhi then said to Liu Bei, “I have contained the rebels here; meanwhile, Zhang Liang and Zhang Bao are in Yingchuan, contesting with Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun. Take your men, and I shall send one thousand imperial soldiers to accompany you into Yingchuan to gather intelligence and plan their capture.” Accepting the command, Liu Bei led his force by night toward Yingchuan.

Meanwhile, Generals Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun—leading the imperial armies—found that the rebels had taken refuge in a grassy, hastily assembled camp in the plains of Changshe. They conferred, “Since the enemy is lodged in the grass, we shall employ fire as our weapon.” They ordered each soldier to bundle a handful of grass and secretly concealed these bundles. That very night, as a fierce wind arose, shortly after the second watch, they set the grass ablaze. Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun then led their troops in an all-out assault; flames leapt toward the heavens, and the terrified rebels, bereft of control over their mounts and their armor in disarray, scattered in all directions.

At daybreak, Zhang Liang and Zhang Bao, commanding the remnants of the defeated rebels, led a desperate retreat. Suddenly, a unit of cavalry bearing red banners intercepted their escape. Leading the charge was a general—a man seven feet tall with narrow, piercing eyes and a long, graceful beard, who held the rank of Cavalry Captain and hailed from Qiaogun in Peiguo—surname Cao, given name Cao, courtesy name Mengde.

Cao Cao’s story began with his father, Cao Song, who originally bore the name Xiahou. Because he was adopted by the eunuch Cao Teng, he adopted the surname Cao. Cao Cao, as a child known also by his diminutive “A-man” and an alternate name “Jili,” delighted in hunting, dancing, and melodious song; he was cunning, resourceful, and always plotting. One day, an uncle, weary of Cao Cao’s unruly behavior, admonished him before reporting his misdeeds to Cao Song. When Cao Song confronted his nephew, Cao Cao quickly devised a clever ruse: as his uncle approached, he pretended to suffer a stroke and collapsed. Alarmed, his uncle rushed to inform Cao Song, who inspected him and found no harm done. “Are you not recovering from your stroke?” Cao Song queried. Cao Cao replied, “I have never suffered thus; it is only that my uncle’s disfavor has left me unheard.” Satisfied by his answer, Cao Song dismissed the matter—and henceforth, Cao Cao roamed nearly unchecked. At the time, a certain man named Qiao Xuan remarked, “In these turbulent times, only one of extraordinary talent can save the realm. Such a person must be the sovereign.” Similarly, He Yong of Nanyang declared, “When the Han falls, the one who can restore order will be none other than you.” Renowned for his insight, Xu Shao of Runan was also consulted; when Cao Cao inquired, “What sort of man am I?” Xu Shao replied, “You are a capable minister in peace and a cunning hero in chaos.” Thrilled by this recognition, Cao Cao, at the age of twenty, was recommended as a paragon of filial piety and integrity, appointed as an attendant, and later designated as the Inspector of Luoyang’s northern district. Upon taking office, he immediately set up rods of five colors at the county’s four gates to enforce the law, punishing even the influential without fear. One night, when a relative of the eunuch Jian Shuo was seen prowling with a knife, Cao Cao patrolled, arrested him, and reprimanded him with his rod. Henceforth, no one dared defy the law—his reputation spread far and wide.

Later, as the Yellow Turban uprising intensified, Cao Cao was appointed Cavalry Captain at Dunqiu. Seizing the moment, he led a force of five thousand—both cavalry and infantry—to Yingchuan to support the fight. As Zhang Liang and Zhang Bao’s forces crumbled in retreat, Cao Cao intercepted them with a fierce counterattack. In a short span, he beheaded over ten thousand rebels and captured countless banners, golden drums, and horses. Though Zhang Liang and Zhang Bao had fought desperately to escape death, Cao Cao then encountered Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun and promptly led his forces in pursuit, assailing the remnants of Zhang Liang and Zhang Bao.

Meanwhile, Liu Bei, having led Guan Yu and Zhang Fei to Yingchuan, soon heard the clashing of arms and saw the glow of fires that lit up the night sky. Hastily, they advanced—but by the time they arrived, the rebels had scattered. Liu Bei explained the matter fully to Huangfu Song and Zhu Jun, recounting Lu Zhi’s misadventure. Huangfu Song remarked, “Now that the forces of Zhang Liang and Zhang Bao are spent, they will surely retreat to Guangzong under Zhang Jiao’s banner. Liu Bei, you must ride out tonight to assist them.” Accepting the commission, Liu Bei gathered his men and turned back. Halfway along the road, they found a detachment of soldiers escorting a wheeled carriage. To their astonishment, inside the carriage was none other than General Lu Zhi. Dismounting in alarm, Liu Bei urgently inquired about the cause. Lu Zhi explained, “I was besieging Zhang Jiao—victory was within reach—but Zhang Jiao’s sorcery foiled us. Later, a court messenger named Zuo Feng arrived to inspect my camp and demanded bribes. I replied, ‘Our provisions are scarce; how can we lavish funds on an envoy of Heaven?’ Offended, Zuo Feng reported that I had labored in vain, demoralizing my men. In his anger, the court sent General Dong Zhuo to seize my forces and escort me to the capital for punishment.” Upon hearing this, Zhang Fei was incensed and threatened to execute the escorting soldiers to save Lu Zhi. Liu Bei quickly intervened, “The court will render its own judgment—do not act rashly!” Surrounded by soldiers, Lu Zhi was led away. Guan Yu then lamented, “Now that Lu Zhi has been captured and another leads the troops, we have no hope here; it is best that we return to Zhuo County.” Liu Bei, conceding to Guan Yu’s counsel, led his men northward. After scarcely two days’ journey, a tremendous clamor arose from behind the mountains. Climbing atop a high mound with Guan Yu and Zhang Fei at his side, Liu Bei surveyed the scene: the imperial forces lay in disarray, the hills behind were swarming with enemy soldiers, and yellow turbans blanketed the land, emblazoned with the words “General of Heaven.” Liu Bei proclaimed, “That is Zhang Jiao! We must engage without delay!” The three heroes spurred their horses and charged forth. At that very moment, as Zhang Jiao had been fighting Dong Zhuo, he now encountered these men in fierce combat—his forces fell into utter chaos and were forced to retreat for over fifty li.

The three heroes then rescued Dong Zhuo and escorted him back to camp. Dong Zhuo asked them their present status; Liu Bei replied, “We are but common men.” Dong Zhuo regarded them with scorn, offering no courtesy. Exiting the assembly, Zhang Fei raged, “We have risked our lives in battle to save him, yet he repays our loyalty with contempt! Unless he meets his fate, my anger will not subside!” Brandishing his blade as he prepared to storm Dong Zhuo’s quarters, he seemingly echoed the timeless sentiment:

In matters of pride and shifting fate,

Who among us recognizes the true hero?

Oh, how I long for a man as resolute as Yide,

To expunge from the world all treachery and ingratitude!

What ultimately became of Dong Zhuo’s destiny, we shall leave to unfold in the chapters that follow.