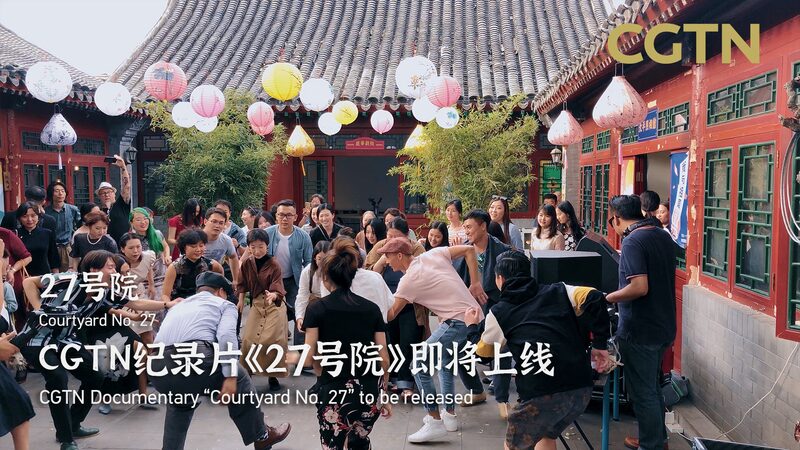

In the labyrinthine alleyways of Beijing's hutongs, 79-year-old Zhu Maojin embodies living history. Born and raised in these traditional courtyard homes, he recalls Spring Festivals of his youth as rare moments of abundance:

"New cloth shoes, pork dumplings steaming in the pot – we waited all year for that joy,"he says, his voice warm with memory.

Today, as high-rises encircle his neighborhood, Zhu observes how modernization has transformed Lunar New Year celebrations.

"My grandchildren video-call relatives abroad while decorating digital red lanterns on their phones,"he laughs. Yet through these changes, he insists the festival's essence remains unchanged:

"However you celebrate, the table must have space for every family member."

Urban planners note that only 1,027 hutongs survive in central Beijing, down from over 3,000 in the 1950s. Cultural preservationists argue these neighborhoods maintain social cohesion, particularly during festivals that emphasize multigenerational bonds.

As night falls on February 12, 2026, Zhu's family gathers around a table laden with jiaozi and nian gao. The electric heater hums where a coal stove once smoked, but the laughter echoing through the courtyard carries centuries of tradition into China's future.

Reference(s):

A very hutong Spring Festival: Family, tradition, and memories

cgtn.com