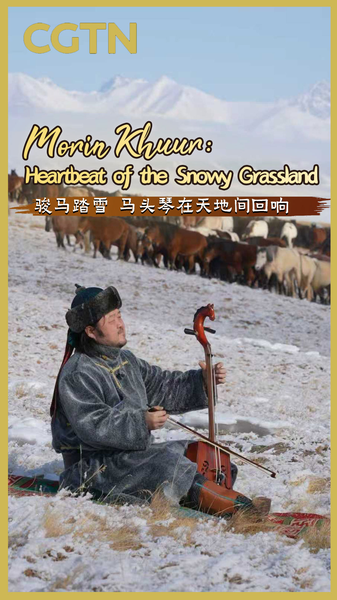

On the windswept Bayanbulak Grassland in China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the haunting melodies of the morin khuur – Mongolia's iconic horse-head fiddle – resonate like a conversation between earth and sky. For master performer Sambuu, this two-stringed instrument serves as both ancestral compass and modern-day storyteller, its carved horsehead scroll bearing witness to centuries of nomadic wisdom.

"When I play for the mountains and herds, I feel my ancestors' hands guiding the bow," says Sambuu, whose performances unfold beneath dramatic cloudscapes. The instrument's distinctive sound – simultaneously mournful and triumphant – mirrors the grassland's own rhythms: the percussion of hooves on frozen earth, the whistling winter winds through snow-laden passes.

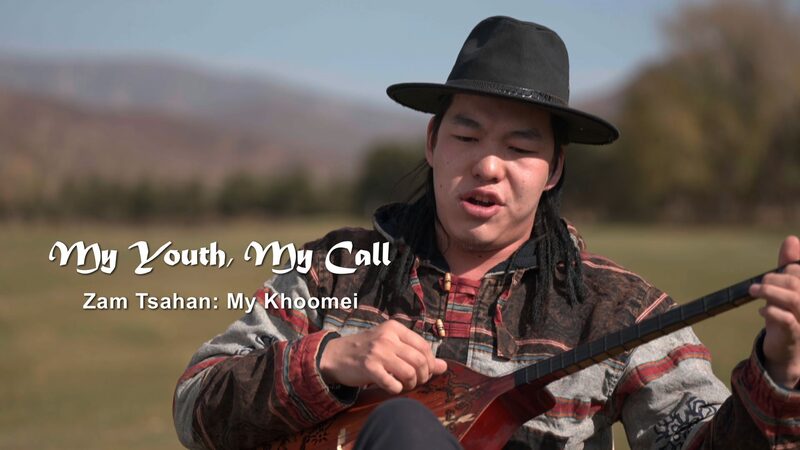

Cultural preservationists note renewed interest in the morin khuur among younger generations, with workshops in regional capitals teaching both traditional techniques and contemporary fusion styles. This resurgence comes as China implements cultural heritage protection measures across ethnic minority regions, safeguarding intangible assets while promoting sustainable tourism.

For global musicologists, the instrument's construction – using horsehide, birch wood, and horsetail hair – represents an acoustic marvel shaped by Mongolia's pastoral traditions. Its repertoire spans from ancient epic poems to modern compositions addressing climate change on the steppes.

As dusk paints the Tianshan Mountains in violet hues, Sambuu's final notes linger like mist over the grassland. In this fragile ecosystem where tradition meets modernity, the morin khuur remains Mongolia's unwavering voice – a bridge between worlds, resonating far beyond the snowy plains.

Reference(s):

cgtn.com