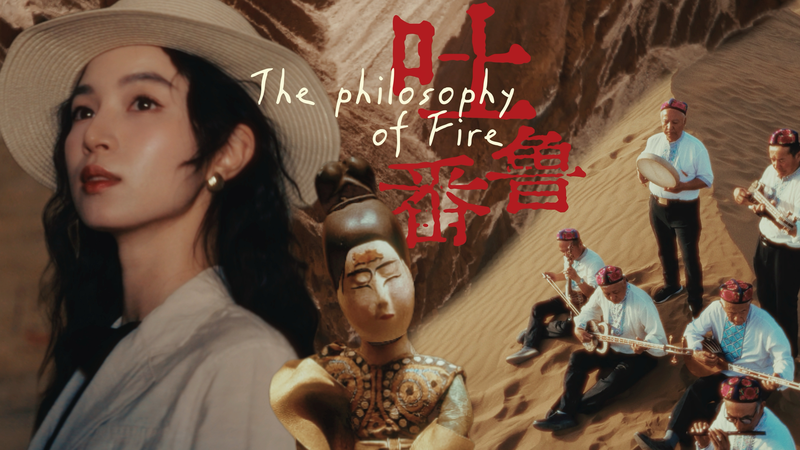

Deep within the arid landscapes of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the Kizil Cave—China's earliest Buddhist grotto—stands as a silent chronicler of cultural fusion. Its walls, adorned with vibrant murals dating back to the 3rd century, depict musicians playing instruments like the angular harp and lute, echoing melodies that once traversed the Silk Road.

Archaeologists identify these artworks as evidence of Xinjiang's historical role as a crossroads for ideas, goods, and artistic traditions between China, India, and Central Asia. 'The diversity in clothing and instruments reflects a cosmopolitan society,' explains Dr. Li Wei, a cultural historian. 'This was not just trade—it was a dialogue of civilizations.'

Yet the cave's story carries complexity. Scars from past excavations mark sections where murals were removed, highlighting challenges in preserving this UNESCO-recognized site. Recent conservation efforts led by Chinese authorities aim to stabilize remaining artworks using 3D mapping, offering new insights into the region's multicultural legacy.

For modern travelers and scholars alike, Kizil serves as both a window into ancient exchange networks and a reminder of heritage's fragility. As restoration continues, the cave's stone symphony grows louder, inviting the world to listen.

Reference(s):

cgtn.com