2026 Winter Paralympics Flame Lit in Stoke Mandeville, Torch Relay Begins

The flame for the 2026 Milano Cortina Winter Paralympics was lit in Stoke Mandeville, marking the start of an 11-day torch relay across Italy ahead of the March 6 Opening Ceremony.

China’s Dazzling ‘D-Moon’ Lights Up Night Sky in Rare Celestial Display

Stargazers in China captured the brightest first quarter moon of 2026, a rare ‘D-Moon’ event caused by lunar perigee, offering a celestial spectacle.

Chang Bingyu Makes Snooker History with Four Consecutive Centuries at Welsh Open

Chinese snooker star Chang Bingyu stuns Shaun Murphy with four consecutive century breaks at the 2026 Welsh Open, advancing to the next round.

Trump’s Record-Long 2026 State of the Union Address Sparks Political Divide

President Trump delivers longest State of the Union address in 60 years amid declining approval ratings and heightened political divisions, with implications for US-Asia relations.

Wang Chuqin Dominates at WTT Singapore Smash, Advances to Last 16

World No. 1 Wang Chuqin leads Chinese charge at WTT Singapore Smash, securing a spot in the last 16. Key matchups set for upcoming rounds.

Discover Chongqing: Where Futuristic Skylines Meet Ancient Heritage

Chongqing’s 2026 allure lies in its fusion of cutting-edge architecture, preserved history, and bold flavors, positioning it as Asia’s must-visit vertical metropolis.

Merz’s China Visit Strengthens Sino-German Economic Ties

German Chancellor Merz leads major business delegation to China, aiming to strengthen trade ties and economic cooperation amid record bilateral trade figures.

Beijing’s Caochang Hutong Finds Balance in Community-Driven Parking Solution

Beijing’s Caochang Hutong addresses parking shortages and exercise facility demands through inclusive community surveys, reflecting China’s governance focus on public welfare.

China Vows to Protect Enterprise Rights Amid Panama Canal Port Dispute

China reaffirms commitment to protect enterprise rights after Panama takes control of two key canal ports operated by a Hong Kong-based conglomerate.

U.S. Lawmaker Ejected During Trump’s 2026 Address Over Protest Sign

A U.S. lawmaker was removed from President Trump’s 2026 State of the Union after displaying a protest sign referencing a controversial social media post.

Breakthrough in Mosquito Repellent Research Offers Eco-Friendly Solutions

A new study identifies a mosquito receptor enabling repellent avoidance, paving the way for eco-friendly solutions to combat diseases in Asia and beyond.

Pentagon Demands Anthropic Drop AI Restrictions by Friday Amid National Security Push

US military demands AI firm Anthropic remove ethical restrictions by Feb 27 deadline, threatening emergency powers enforcement amid national security concerns.

AI Companions Bridge Cultures Through Chinese Heritage in 2026

CGTN’s 2026 ‘Ask China’ campaign uses AI virtual companions to make Chinese culture interactive and educational for global audiences.

Trump Stresses Diplomacy in Iran Talks During 2026 State of the Union

President Trump emphasizes diplomatic resolution with Iran during 2026 State of the Union address, signaling potential shift in Middle East strategy.

German Chancellor Warns Against Decoupling from China: ‘Shooting Ourselves in the Foot’

German Chancellor Merz warns against economic decoupling from China ahead of key trade mission, emphasizing interdependence and shared opportunities.

China Advocates Political Resolution to Ukraine Crisis at UN

China reaffirms commitment to political resolution of Ukraine conflict during UN vote, advocating multilateral dialogue and sustainable security frameworks in 2026.

German Chancellor Merz Begins Key China Visit to Strengthen Economic Ties

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz begins crucial 2026 Beijing visit to boost economic cooperation and green energy collaboration with China.

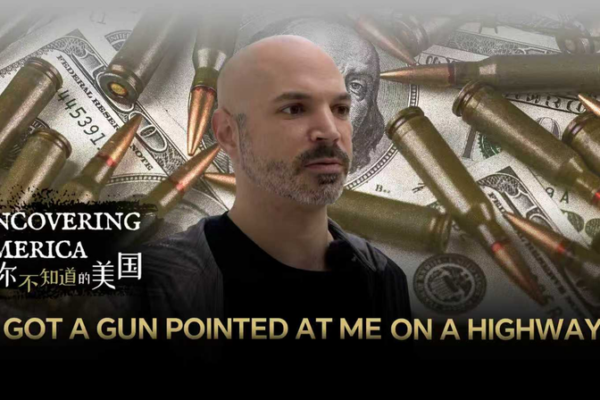

Rising Emigration Trends: Americans Seek Safety Abroad Amid Gun Violence Concerns

A recent Gallup survey reveals 1 in 5 Americans consider emigrating, citing gun violence and political tensions as key factors driving their decisions.

AMD Secures $60B AI Chip Deal with Meta, Intensifying Industry Competition

AMD’s $60B AI chip supply deal with Meta highlights growing competition in the semiconductor sector as tech giants race to secure hardware for AI infrastructure.

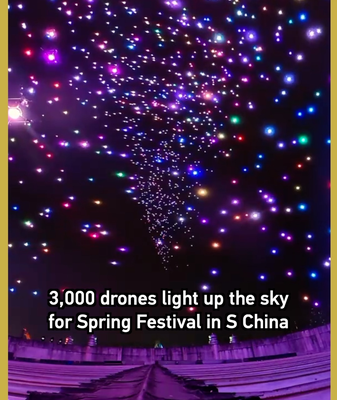

Nanning’s 3,000-Drone Spring Festival Spectacle Blends Culture and Innovation

Nanning dazzles with 3,000-drone light show blending traditional Spring Festival motifs with cutting-edge aerial technology in 2026 celebration.