Global Governance at a Crossroads: Unity vs. Survival of the Fittest in 2026

As 2026 unfolds, China’s Global Governance Initiative challenges unilateral power politics, offering a vision of shared global prosperity amid rising tensions.

China Sets 2027 Deadline for Low-Altitude Economy Standards

China announces plans to establish a standardized framework for its low-altitude economy by 2027, covering aircraft, infrastructure, and safety systems to support industrial expansion.

China-Built Desert Railway Boosts Algeria’s Economy, Connectivity

Algeria inaugurates Africa’s first Chinese-built heavy-haul desert railway, enhancing mineral transport and cross-regional connectivity amid Sahara Desert challenges.

Antarctic Volcano Catalog Unveiled in Groundbreaking Study

International scientists unveil first comprehensive catalog of 207 Antarctic subglacial volcanoes, enhancing climate prediction capabilities and ice sheet research.

China Greenlights Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Spatial Plan Through 2035

China approves a long-term spatial plan to boost integrated development in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, focusing on infrastructure, innovation, and sustainability.

Chinese Premier Stresses Smart Manufacturing, Green Energy in Shandong Tour

Premier Li Qiang outlines strategies for technological innovation and sustainable energy during Shandong inspection, emphasizing growth and public welfare.

Greenland PM Slams U.S. Over ‘Divisive’ Policies, Seeks Dialogue

Greenland’s PM condemns U.S. pressure over territorial ambitions, reaffirms sovereignty, and announces diplomatic efforts to resolve tensions.

Trump Confirms Ongoing Talks with Iran Amid 2026 Tensions

U.S. President Trump confirms ongoing negotiations with Iran in 2026 amid naval deployments, with Asian markets monitoring potential regional impacts.

Israel and U.S. Conduct Red Sea Naval Drill Amid Rising Iran Tensions

Israeli and U.S. navies complete joint Red Sea drill amid escalating regional tensions with Iran, highlighting strategic maritime cooperation.

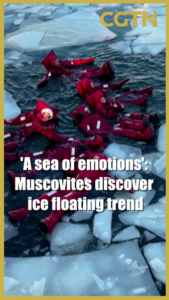

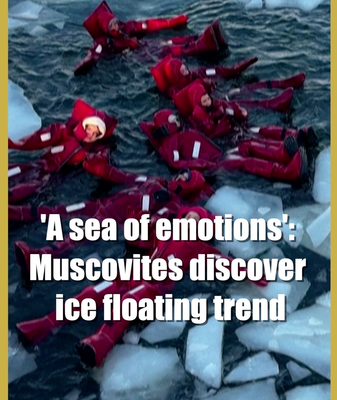

Ice Floating Gains Momentum in Moscow as Winter Activity Captivates Residents

Moscow residents embrace ice floating in frozen rivers as new winter wellness trend, combining traditional Russian practices with modern urban adaptation.

Taiwan Entrepreneur Bridges Culinary Divide in Beijing

Taipei entrepreneur Kuo Wen-yu builds Beijing-Taiwan food supply chains, blending culinary traditions while fostering cross-strait economic ties.

China’s Spring Festival Rush Blends Travel with Cultural Heritage

China’s 2026 Spring Festival travel rush begins, merging mass mobility with intangible cultural heritage experiences at major hubs like Zhengzhou East Railway Station.

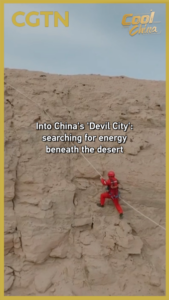

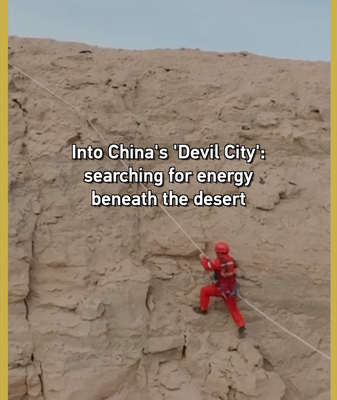

China’s ‘Devil City’ Holds Key to Energy Future

Geophysical teams in Qinghai’s ‘Devil City’ brave harsh conditions to map deep energy reserves, signaling China’s push for sustainable resources ahead of Spring Festival 2026.

China Condemns U.S. Detention of Chinese Business Personnel

China criticizes U.S. detention of Chinese company staff, urging immediate cessation of ‘unjustified’ enforcement actions amid rising bilateral tensions.

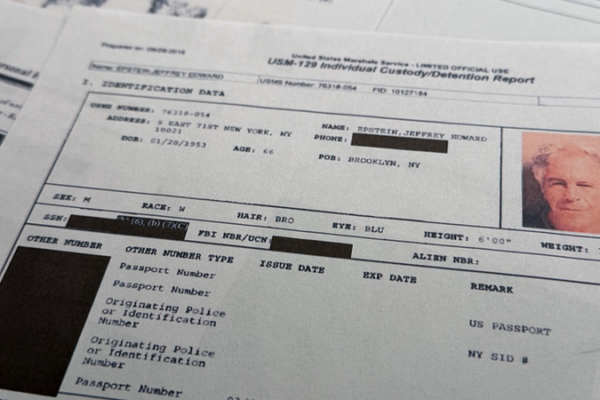

Epstein Files Fallout: Asian Leaders, Global Figures Deny Links Amid New Revelations

Newly released Epstein documents prompt denials from Malaysian PM Anwar Ibrahim, UK ex-ambassador Peter Mandelson, and LA Olympics chief Casey Wasserman, while Elon Musk addresses email revelations.

China Intensifies Cross-Border Crackdown on Telecom Fraud, Executes Myanmar-Based Gang Leaders

China executes Myanmar-based fraud ring leaders, reports $2.3B recovered in multinational anti-crime operations as cross-border law enforcement cooperation intensifies.

Rafah Border Reopens Amid Fragile Gaza Ceasefire

Israel reopens Gaza’s Rafah crossing with Egypt for limited movement amid ongoing violence and US-brokered ceasefire efforts.

Cyclone Fytia Claims 7 Lives in Madagascar, Displaces Thousands

Cyclone Fytia leaves 7 dead, displaces over 54,000 in Madagascar as authorities assess damage and coordinate relief efforts.

China Unveils 2026 Spring Festival Consumer Boost Plan

China launches a multi-sector initiative to stimulate Spring Festival 2026 spending, targeting tourism, retail, and entertainment to drive economic growth.

Lagos Tech Summit Spotlights Africa’s Impact-Driven Innovation

The 2026 Tech Revolution Africa summit in Lagos highlights operational tech solutions addressing affordability, energy access, and data-driven growth across the continent.