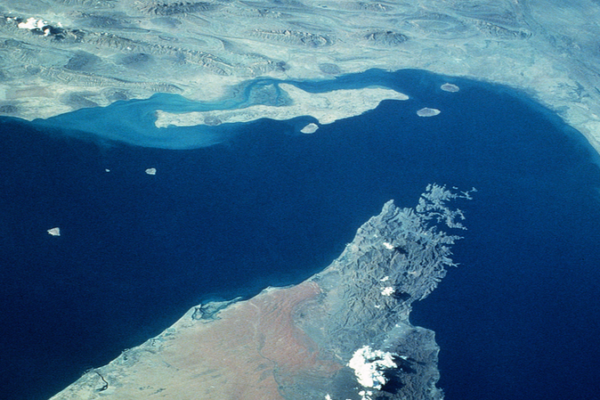

Strait of Hormuz Closure: Global Trade at Risk as Tensions Escalate

Iran’s closure of the Strait of Hormuz threatens 21% of global oil transit. Analysis of historical precedents and current energy market impacts in 2026.

Lantern Festival 2026 Illuminates Cultural Unity Across Asia

Asia celebrates 2026 Lantern Festival with tech-driven displays and cross-regional cultural exchanges, highlighting tradition’s modern evolution.

U.S. Urges Immediate Departure for Americans in Middle East Amid Rising Tensions

U.S. issues urgent travel advisory for 16 Middle Eastern countries, urging Americans to depart immediately amid heightened security concerns.

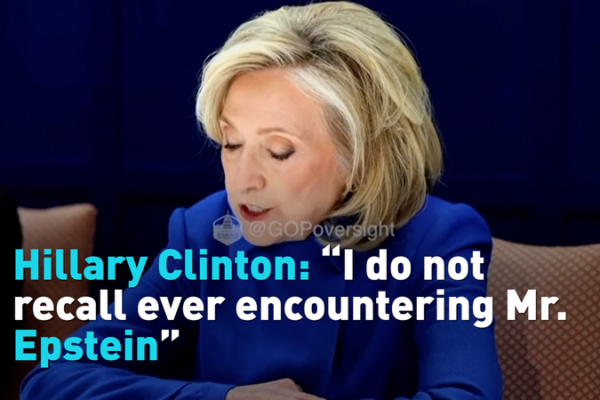

Hillary Clinton Denies Ever Meeting Jeffrey Epstein in Congressional Testimony

Former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton testifies before Congress, denying any encounter with late financier Jeffrey Epstein during March 2026 hearing.

Escalating Tensions: Lebanese Civilians Flee Amid Israeli Airstrikes

Hundreds of Lebanese civilians evacuate border areas as Israeli airstrikes escalate regional tensions, raising humanitarian concerns.

US-Iran Tensions Surge as Trump Authorizes Expanded Military Strikes

President Trump’s expanded military strikes against Iran in 2026 escalate tensions, raising concerns over regional stability and congressional oversight.

Two Sessions 2026: Navigating China-US Relations in a Shifting Global Landscape

As China’s Two Sessions convene in 2026, global attention turns to the evolving dynamics of China-US relations amid trade uncertainties and geopolitical shifts.

Brazil’s Iranian Diaspora Voices Concern Over Middle East Tensions

Iranian diaspora in São Paulo expresses concern over escalating U.S.-Israel-Iran tensions, advocating for diplomatic solutions and peace in 2026.

Iran Condemns Alleged Plot Against Supreme Leader Amid Rising Tensions

Iran accuses foreign actors of targeting Supreme Leader Khamenei as the US denies involvement, escalating regional tensions in March 2026.

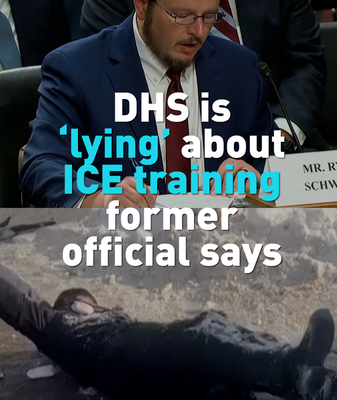

Ex-ICE Official Alleges DHS Misled Public Over Training Flaws

Former ICE attorney Ryan Shwank testifies before Congress, alleging DHS misrepresented flaws in agent training programs. March 2026 hearing sparks calls for reform.

Iran FM Warns of ‘No Victory’ in U.S. Tensions Ahead of Geneva Talks

Iran’s Foreign Minister warns of devastating consequences from U.S. conflict, as both sides prepare for Geneva talks aimed at easing regional tensions.

Deadly Cuba-US Boat Incident Sparks Diplomatic Tensions

A deadly clash between Cuban border agents and a speedboat near Havana has escalated tensions between Cuba and the U.S., with both sides demanding accountability.

Canada Boosts Food Aid to Cuba Amid US Fuel Blockade

Canada pledges $8M food aid to Cuba as US fuel blockade intensifies, highlighting global tensions over Caribbean stability.

Middle East Escalation Puts Civilians in ‘Grave Danger,’ Red Cross Warns

ICRC warns of devastating civilian consequences as Middle East military escalation triggers dangerous chain reactions in 2026 conflicts.

UAE Airports Restart Limited Flights Amid Gulf Security Concerns

UAE resumes limited airport operations after Iran-linked security closure, easing travel disruptions while maintaining heightened safety measures amid Gulf tensions.

Spain Blocks US Use of Military Bases for Iran Strikes, Stresses Sovereignty

Spain denies U.S. use of its military bases for strikes on Iran, emphasizing sovereignty and UN compliance amid escalating Middle East tensions.

Iran Navigates Leadership Crisis Amid Regional Tensions

Iran activates constitutional protocols after Supreme Leader Khamenei’s death, balancing governance transition with military response to regional strikes.

UK Prioritizes Diplomacy Over Military Action in Iran Crisis

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer defends diplomatic approach to Iran tensions, emphasizing defensive measures and international law amid US criticism.

Energy Prices Surge, Global Markets Slide Amid Iran Conflict Fallout

Global energy prices spike and stock markets tumble as Iran conflict escalates, disrupting key trade routes and investor confidence in 2026.

Deadly Clash in South Sudan’s Ruweng Leaves 169 Dead, Peace Deal Strained

At least 169 killed in Ruweng Administrative Area attack, raising concerns over South Sudan’s fragile peace process. Children, officials among victims.