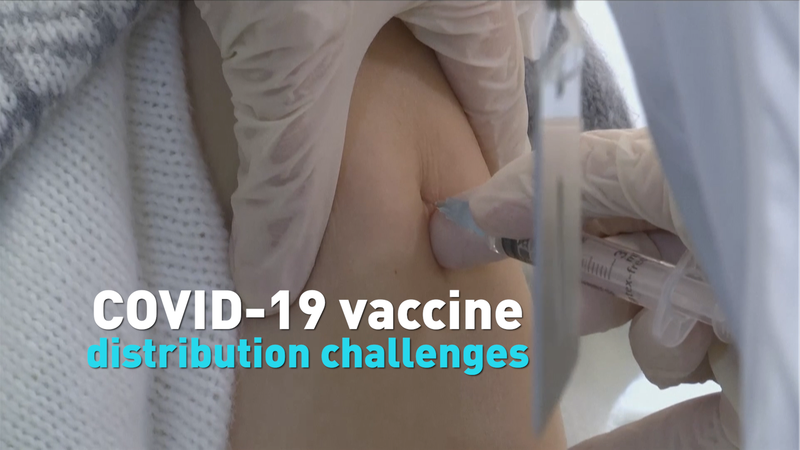

At Denver’s National Western Complex, thousands of individuals, primarily over the age of 70, recently received their first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. For many, this moment couldn’t come soon enough.

“I want to see my grandchildren and hug and kiss them, and I can’t,” said vaccine recipient Ruthie Stoner. On that day alone, 5,000 shots were administered.

“This is our way out of the pandemic—to get everybody vaccinated,” stated Dr. J.P. Valin, Chief Clinical Officer of SCL Health. The health system organized the event specifically to reach vulnerable populations in communities of color.

“We are more likely to be infected but also more likely to be hospitalized and more likely to die,” emphasized Deidre Johnson, CEO of the Center for African-American Health.

Government statistics reveal that Black and other people of color die from COVID-19 at rates nearly three times higher than whites. Yet, a Kaiser Family Foundation survey of 23 states indicates that Black individuals lag well behind the general population in receiving the vaccine.

“No one is running towards vaccines,” Johnson noted. “We just happen to be a group that has historical reasons for that mistrust.”

The mistrust stems from a long history of medical mistreatment, such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, which have fueled deep unease among African-Americans towards the medical profession. Access to healthcare remains a significant issue, and the rapid development of the vaccine under Operation Warp Speed has also contributed to vaccine hesitancy.

“All that kind of creates a haze around making this decision, and so we’re working to, as they say, clear that haze,” Johnson said.

In response to these challenges, the White House’s COVID-19 Task Force announced plans to deliver vaccine doses to federally funded clinics in underserved areas. Community health centers in states like Texas are currently inoculating majority minority patient populations.

“There are a whole bunch of strategies that we’re going to need to take to be able to reach this community,” Dr. Valin explained. “There’s not a one-size-fits-all solution for reaching this population.”

SCL Health collaborated with more than three dozen organizations for its vaccination event, including those serving the LGBTQ community.

“The last few months have been very difficult for me,” shared vaccine recipient Ron Zutz, reflecting on his isolation. “I have never been so excited to have a stranger stick me with a sharp object.”

“Many folks from the LGBTQ community are part of the service industry or retail workers or frontline workers,” said Rex Fuller, CEO of The Center on Colfax.

The same is true for the Black community, contributing to their already heightened medical risk and underscoring the urgency of vaccine distribution. By getting doses to those who need them most, communities hope to bridge the vaccine racial gap and reunite families.

“I’m just over the moon,” Stoner expressed joyfully. “I’ll be able to hug ’em and kiss ’em. Oh, I’m just looking so forward to that.”

Reference(s):

cgtn.com